Perhaps the supreme irony of black American existence is how broadly black people debate the question of cultural identity among themselves while getting branded as a cultural monolith by those who would deny us the complexity and complexion of a community, let alone a nation. If Afro Americans have never settled for the racist reductions imposed upon them -- from chattel slaves to cinematic stereotype to sociological myth -- it's because the black collective conscious not only knew better but also knew more than enough ethnic diversity to subsume those fictions. -- Greg Tate

If you and I had quite enough time together, I am certain I could get you to a place where you could understand clearly a good deal about the culture and times that have produced in me an appreciation for some critically important supranational values that have taken me far from where I started. Still that wouldn’t be so far. Then again if you turn your back to a mirror it ceases to function. If you love your face and possess self-confidence you needn’t spend so much time.

What now begins, under the aegis of my responsibilities to Free Black Thought, of which I am a co-founder, to illustrate some things I think are important, which is a kind of journey through blackness which is at once personal & individualistic yet readily understandable and familiar to Americans. Since I intend to add a heaping helping of truth, I expect it to be something everyone can know. Not just savoir but connaître.

The reason for this originates in the desires that I’ve had combined with some questions I was asked but could not answer satisfactorily in the extraordinary New Alliances Conference I attended in NYC this month. One question came from Mark and the other from Liang. My own interest is simple. I’d like to investigate the series of aha moments when various black Americans determine when they own blackness but blackness doesn’t own them. The ramifications of answering these are complex and I’m not exactly sure how I can keep my writing clear on this. Then again, you know how I connect concepts. But here’s the best way to consider the entire matter. We are on a journey from home ground to common ground to higher ground. There are some fairly specific skills and methods to accomplish that are in many ways parallel to disciplining The Epistemics. But I’m not trying to write a book here.

Mark’s Question: Disaggregation

Mark and I are about the same age. He works for a DC think tank and he’s having a hard time disaggregating black Americans in the main. It’s relatively easy, he says, to rule out the West Africans and the Caribs when you focus on the socio-economics, but as often as it is said that ‘we are not a monolith’ it can look awfully monolithic to outsiders. So how does one navigate that non-monolith?

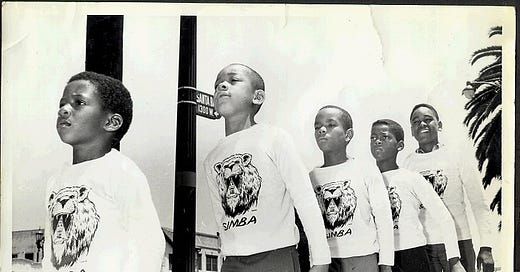

I have the extraordinary fortune of having been born a Negro and understood that change was happening in the 1960s. Even as a school age child, I knew that Black Consciousness was being invented by people like my father. I knew my uncle was a PhD and college administrator who lived in a large brick house in Cleveland Heights. I knew my other uncle and his family made many trips to West Africa with the Peace Corps, and so I studied French and Swahili, waiting for the one day. I knew we took a passport photo and would have to get shots if we were going to move to Accra or Brazilia. I knew Dr. Alfred Ligon who owned the first black bookstore in California as well as the Hall family who owned another prominent bookstore over on Santa Barbara Blvd., which eventually became one of the first if not the first major street in America to be renamed after MLK. The Hall’s adopted daughter was Judy Milliken, my 5th and 6th grade teacher who was a USC graduate and was white. I loved her, she was my favorite teacher, and so I can never use her name again on security questions. I also was a Young Simba and my family hosted the very first Kwanzaa Karamu. Yes of course we knew Ron Karenga whose US organization met in Ligon’s Aquarian Center, also on Santa Barbara Blvd. That’s me, first in line, for a photoshoot that made the cover of Look Magazine.

When you give up Christmas as a child and hear Swahili around the house in the 1960s, you gain something I call ‘black credibility cookies’. If you understand the context in which the Black Nationalist, Black Arts & Black Consciousness movements were undertaken, you understand how powerful such credibility is. At the same time, if you belong to a family that never taught or preached hatred or violence, you just as easily understand how there were ideological conflicts between us and the Nation of Islam and Black Panthers. The varying successes and failures of these threads of intellectual, political and cultural developments were never far from our minds. Our families made hard choices. Various Negro churches wanted nothing to do with blackness. Others, like that led by Father H. Belfield Hannibal were forward thinking. When Negro Digest changed its name to Black World, it was in acknowledgement of Pan-Africanism which was part of a larger movement as post colonial African territories gained independence. But most importantly to me as a young man, I understood that there was always a strong evangelical aspect to all of these movements. There was always a Black vanguard telling the Negro that he was asleep. Sound familiar?

I understood that I was part of that element of the American population known as the Talented Tenth. As such, we had certain prerogatives. What almost nobody speaks about, but certainly Bertrand Cooper knows clearly is that when it comes to income and wealth inequality, the black American 1% is more unequal to black Americans than the American 1% is to all Americans. As was well understood to all of us convinced an international [Marxist] revolution was coming, whether or not it would be televised, some of us peasants would be made into rulers. When you’re 11 years old, it means you know every word in every stanza of the Black National Anthem, and by god you’re going to teach them. If you read all of the words, you come to understand that this poem exists as a fait accompli. When performed however, you almost never get past the first stanza which begs questions answered in the second and third. Here in the second is the declaration not of marching on until victory is won, but standing in the truth of victory:

We have come over a way that with tears has been watered, We have come, treading our path through the blood of the slaughtered, Out from the gloomy past, Till now we stand at last Where the white gleam of our bright star is cast.

The Slave is slaughtered. The Negro is dead. We Blacks stand in the light. I thought you knew. Well I guess it’s our job to save the rest of you Juneteenth stragglers, shiftless Negroes and racist rednecks before you set the race back 100 years.

Ask enough black Americans in the working class, middle class, the affluent and the wealthy and you will always find similar tales of evangelism that endeavor to save those one class beneath us. This is the black American dream within the American dream. For most of our history here, I am bold to say we never expected that anyone else would have a desire to take up such a burden. I have mentioned before that black culture embraces that collection of social strategies and tactics, the Greenbook roadmaps to success. So what you listen for is those who seek to keep marching until victory is won. Or you listen for those who have decided this burden will never be raised and have given up all hope. Somewhere along that spectrum of the desire for racial uplift are the boundaries of the monolith.

I say the black monolith is composed of those marching on in solidarity with those others, the lesser of our brothers who exhibit for whatever reason those desperate dysfunctions, faults & frailties of the eternal emblematic uncles, poor cousins and disrespected of America. It is to this evangelical beat of waking up for which ‘allies’ are sought and bona fides granted for that great mission with all of its promise and potential. Who could resist such a calling? The talismans of this ambition fits very comfortably in the various pockets of International Marxism, of liberation theology, of ethnic nationalism, of community outreach, of Affirmative Action, of Keynesian economics, of Progressive politics and of course the new Woke Religion.

Black Americans suffer like any other human beings, but the very success of the creation of blackness makes that suffering especially poignant and symbolic of the moral aims of humanism.

It is only the ability to walk aside all of those enticements understanding the context of their creations that disambiguates that which is objectively ethical from a Enlightenment liberal humanist point of view from that which requires racial essentialism to put some special hot sauce on the same calories. Black Americans tell on themselves when they emphasize their flavor. The monolith exists to the extent that those in possession of cultural roadmaps do not generalize its wisdom and only seek a racially restricted application of its benefits, as if jazz music should only be heard by blacks.

So I will be so bold as to say that here is a surefire way to disaggregate the monolith. It has something to do with the ways in which black Americans dither on class division. It pertains to why we bother to identify solidarity with the black homicide victim of police misconduct and not the white victim. It pertains to why we bother to name something Black in our special duties to ‘our people’. That sense of possession of people is so telling. Not ‘the people’ but ‘my people’. Not all lives. Black lives. Not crime. Black crime. Not the acquisition of power. Black empowerment. At some point of wisdom and moral maturity, the self-serving nature of these ‘brotherhoods’ and ‘allyships’ becomes irreversibly transparent.

If this sounds like and indictment, I don’t mean it to be. I mean it, without prejudice to be a way to investigate the ways and means by which nominally black Americans decide to position themselves within nominally black America. As Mark has seen, Caribs and West Africans are much less likely to be racially stingy with their talents. Their families didn’t inherit the American Greenbook, or the Black movements aimed at the Negro. They haven’t spent equal time aiming to merit ‘black credibility cookies’. They are more comfortable in accepting class distinctions within their putative racial caste. We American born all have to reckon a bit more with the energy and conviction we spent in the various movement attempts to transform the entirety of the Negro race in those revolutionary and now more institutional contexts. What kind of people create ‘BIPOC’? Those who desire to unify the black race for the benefit of the black race. This is done, I believe, out of a genuine belief / fear that there is no other way to accomplish progress. It is a racialist fallacy that our Enlightenment liberal principles are having a very tough time transcending in practice. Either way, it preserves and strengthens the black racial monolith. It is the power of the racial fallacy that makes that monolith dangerous to approach.

“What is it like to be a problem?”

If you don’t second guess black Americans then there is no black problem. There is only the Negro Problem as stated above. To engage the movements of the 60s, especially those with international reach and ramifications, is to identify how nominally black Americans determined to change the context by which they decided to behave and be judged. The Negro, by and large, accepted the American definition very much (from what I see) in line with the era of ethnic immigration in the 20th century. What did Irish, Italians, Chinese, Russian Jews, Germans and Poles want in America before the Great Depression? They wanted to join an industrial urban economy from rural roots? Midwestern Scandinavians a bit less, though. I’d say on the whole that is a fair assessment. I’d also suggest that is the arc of the Great Migration from sharecropper South to industrial North for the Negro. Not only a new economic but a new political bargain at arms reach for those who first could only vote with their feet. Those who survived WW1 and the flu pandemic start to resemble my grandparents. From whatever the home ground was, that 20th century common ground was established: civil rights and civil religion, simple natural consequences of the Bill of Rights.

It is the philosophy, religion and politics of the survivors of pre-war families that represents my analytical ground zero. It has long been a baseline assumption for me that few Americans have ever been so destitute as those portrayed in Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath, amazed by the function of flush toilets. By my middle school reading of Tortilla Flat and Cannery Row, I was sick to death of such depressed characters. Teachers wanting me to read Upton Sinclair and Robert Lipsyte was what racism felt like to me when I was 13 and fascinated by nuclear energy and space travel. I already stood in the white gleam of bright stars, and I knew it was fusion.

—

Since I am Stoic and I’m telling first person parables like I’m some kind of cosmopolitan Aesop, I’m going to take the philosophical dimension as the context for an intellectual understanding of how to break up this monolith. So I accept what could be reasonably called selfishness and impatience as a kind of virtue of necessity. I’m not here to confess love or hatred for black people who don’t roll like me. In actuality, my distance and dissonance from blackfolks was and is one born of the impatience of nerds. It’s the same age old egotism of anyone who dares turn their back on the village elder, the neighborhood ‘mayor’, the hawker of populist sentiments. I wanted to be an astronaut. My parents didn’t allow me to watch blaxploitation movies. I think it is sufficient and I’m perfectly happy to let people say I’m a class snob. It’s hardly a nuanced view but go ahead and stipulate it. Either way I have abandoned the specific imprimatur of the Talented Tenth. Not because everybody who doesn’t is absolutely self-serving, but I would feel that I would be self-serving to do so. I don’t see the need for ‘black leaders’ in rather the same way as I don’t see the need for special geography scholars to confront flat earthers. No hot sauce flavored anti-Mercator projections. No Afrolantica Rising.

This leaves us with something unsatisfying. What are we to think of black Americans? I think an evolution of the nagging Negro question helps. Given a non-racial philosophy, the proper question might be, “What is it like to be a socio-economic problem?” Once again my perspective tells me that like the well-intentioned overproduction of the Black movements, social science itself is also responsible for the way we look at this subset of humanity, this demographic fraction of America. Whatever compels us to discount the premise of citizenship in ‘all men are created equal’ is to be suspect. Whatever says we must account for the race of our good works is to be suspect.

If the aim of higher ground is the omnipresence of justice or the preservation of transcendent aesthetics or saving the ecology from devastation, it must build upon the assumptions of common ground of individuals who can take advantage of civil liberties to apply their special skills. Even if there are those who cannot reliably remain at common ground, we cannot disabuse our powers to reach higher ground for the fallacious reasoning of racial solidarity which poisons the very idea of common ground and undermines individuality. So none of us should be racially selfish with our talents because the necessity of common ground demands that we abandon the racialization of human beings.

Some of us so-called blacks understand this to be a necessary individual transcendence. For us it is relatively simple, despite the confusion and conflict it generates, to keep our racial identity at a haphazard distance. We defy racial essentialism. It is simultaneously simple to use cultural idioms of whatever sort of blackness we feel comfortable with. This is a cosmopolitan social skill which deserves respect. In large cities like New York, it’s a useful practicality to tap the table for a refill of tea, or to give two snaps up for the clever riposte or to let the phone go to messages on a Saturday. Somebody gets it.