Deadly Curiosity

Three books. Three warnings.

It’s difficult to make predictions, especially about the future.

— Unpredictable

Of course one of the keywords of this place is Discovery. I see it as part and parcel of understanding the unique breadth and effect of Western Civilization. There are limits. In my curiosity, I want to understand the limits of curiosity. Or another way to put it is the value of conformity. The way I arrange this apparent contradiction in my own life is simple. I want to know how to arrive at a well-trod destination, which is to say that I find it more appealing to raise an existing nation’s flag than to burn it and found a new nation.

Previous to reading the three fictions that are influencing my thinking now, there were two particularly salient novels that properly scared me away from wishful thinking about the future. The first was Jeremy Robinson’s Infinite. The second was Xixin Liu’s Three Body Problem trilogy, specifically The Dark Forest. Both give considerate dramatizations of Western Man in his ultimate achievement of knowledge and/or power in the universe. Both are significantly frightful.

So how do we not kill that cat?

Blood Music

Greg Baer is one of my favorite sci-fi writers. I have read so much of his work that I cannot even categorize him as anything but brilliant. When I read his Eon series it was the first time that I considered how emojis and pictograms might possibly be superior to alphabetic written language.

This book investigates the human biohacking equivalent of Oppenheimer’s Trinity test actually igniting all of the oxygen in the atmosphere. Although it’s slightly dated, it remains a very good terrestrial adventure into weird science. What’s most interesting about the consequences of this invention is that it reveals an actual set of possibilities far beyond the wildest dreams of its inventors. In this, you give someone the opportunity to experiment on themselves and it proceeds marvelously until it doesn’t.

This is a very timely lesson for those interested and invested in superheroes, transhumanism and AGI each of which are seductive but can only deliver on their seductions to the point anyone can imagine. In the same way the results of any revolution cannot be predicted, this miraculous change overproduces. Then one is faced with one’s own ignorance and the unforgivable nature of progress. It’s very interesting when what can be envisioned as ‘incredible progress’ becomes ‘inevitably dislocating change’. Imagine you wanted to be able to see in the dark, or actually have radar and infrared vision. Snap! You now have three eyeballs in your face. Now who’s attractive?

What’s particularly interesting about this story is the extent to which it takes place in isolation in the US at first. As we are fond of saying, the future is already here just unevenly distributed. By what right or motive does any minority of humans define progress according to their own inability to suffer foolishness or hardship?

The unintended consequences of empowerment is really the bottom line in any of these tales. Why do we study the construction of tools of empowerment (all are ultimately weapons) absent the ethical discipline of control? Because we don’t really know if we can control something we intend to transform us.

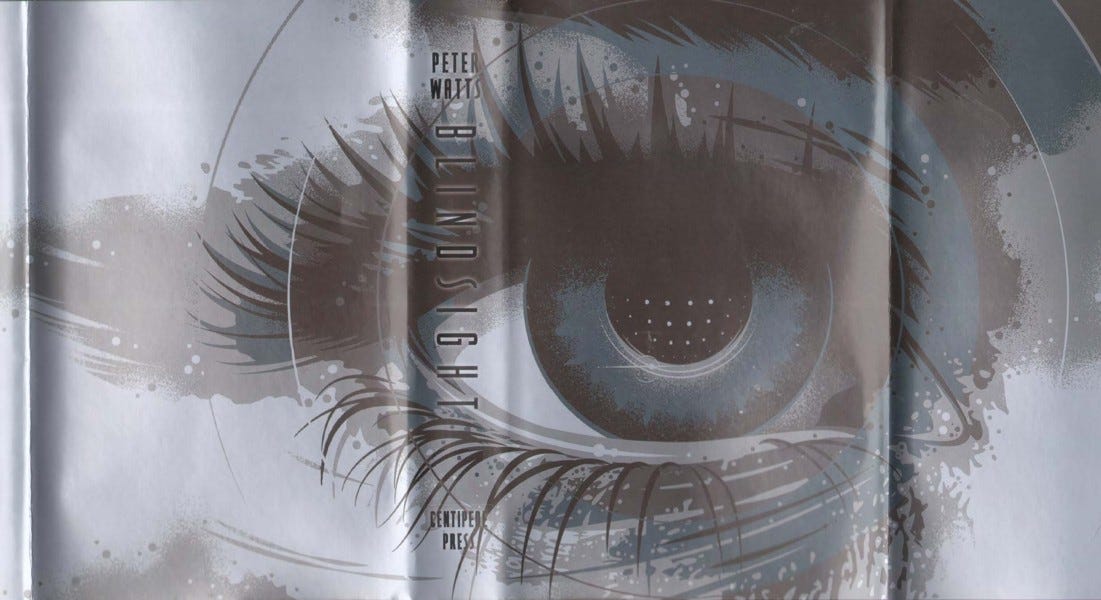

Blindsight

Somewhere in my rambling thoughts about evolutionary psychology and neuroscience I encountered the name of author Peter Watts with a spellbinding mention of his book Echopraxia. This probably came from one of the vanguardians of Deimos Station among whom I am an occasional participant. I’m a bit too Dad Bod to get into all of their particularly intellectual Twister games, but I understand. As I began listening to the audiobook I discovered that it was not lightweight reading and therefore not amenable to the kind of lucid dreaming I can do between 5 and 7am.

Watts is one of those extraordinary individuals who gives fuck all to conventional wisdom and has found a profitable way to communicate rationally plausible arcana into written form. Put another way, let’s compare him to Peter Weir. Weir’s heroes and protagonists are geniuses in ability, but you can easily follow their plot exculpatory inner dialogs. They’re internally nice and patient explainers for the comfort of the reader and thus reading them gives you a little fist bump for being able to guesstimate their general directions. Watts’ characters are impenetrable. They’re have five way conversations each with other genius characters and at least one is considered even more inscrutable.

So Blindsight is a story that begins with a very capable starship, its predator-genius captain and its go-getter crew waking up way off course and encountering something completely alien. My understanding is that the story takes the Chinese Room metaphor into extreme territory as the humans find themselves completely overwhelmed by their inability to conceive of and deal with an alien intelligence that is both incomprehensible to humans and indifferent to human existence. Imagine yourself having a four year old’s conversation with a bowl of cereal. This is what I expect to find from Watts’ Blindsight among other frighteningly cautionary tales. This is especially the case as the narrator of the story has been biologically altered to be incapable of human subjective consciousness. In that way, he may be the ultimate indifferent stoic.

Remembering what little I do from Echopraxia, this is going to be frightful.

Season of Skulls

One of the most hackneyed of fictions is that of time travel. What is extraordinary about its appropriate fictional realization is that we are awful as humans as reliable arbiters of causation and correlation. What we have is Yogi Berra to the third power in reverse. Predicting the past’s influence on the future (our present) is even more impossible than predicting the future because we don’t really know what happened in the past until we get there. Which we cannot, in reality. And did Yogi Berra actually say that about prediction? All that, being as it contingently may, what I do love about author Charles Stross is his uncanny ability to describe the gut dropping sense of fear in his characters.

Additionally, Stross more than any other author I know, has done more to indict US and UK governments in literal deviltry in his fiction. He never forgets the monsters that animate our dubious allegiances as citizens. He’s part author of the punk in me because he doesn’t mind at all being impolitic. So his best characters engage their Lovecraftian fate above and beyond the call of duty and the willingness to cringe and freeze that we would ordinarily do.

In Season of Skulls, his tightly wound female protagonist is placed under a binding magic spell to obey her conniving, tyrannical and kinky billionaire husband who may or may not be dead. Being a part of an old family of non-Muggles, she is privileged to have a few tricks up her sleeve as well as access to her inherited mansion which has a wing that contains portals to various demonic realms, including England’s past. She is now caught between her binding spell and the command of the Prime Minister who is, in actuality, some hellion servant of the Mute Poet, an occult juggernaut of blood curdling power who demands the head of said ex-husband. So she must travel back in time to 1816 or thereabouts to avoid being destroyed.

If you can imagine what it might be like to be Glenn Close transported back to the days when the word of any titled gentleman would suffice to have any woman in chains and off to a nunnery, then you’ll rapidly understand the horror of our heroine’s predicament. In this, her willfulness, her genius and her power are both invaluable strengths and crippling vulnerabilities.

Very much like any proper science fiction we are engaged with a strange world to where we have been conveyed by extraordinary means and must survive its alien threats. In this case that include both practitioners of occult as well as the customs of pre-Victorian England in which women of even the slightest social acceptability could never utter f-bombs, much less wander away from hearth and home unaccompanied.

Stross even goes beyond this to embed a plot within his fiction which he poses as the inspiration for Mary Shelley’s 1818 Frankenstein. Perfect genius.

In Western Civilization, we have perhaps more open source material and possibilities to empower our individual selves than any persons in history. The clever among us have access to institutions which aim to retain that legacy and repository of knowledge. But like the peasants of old we know that power does not necessarily require knowledge, and knowledge does not necessarily yield power. Ironic isn’t it that Donald Trump (I predict) will come up short in the end.

I’ve hinted at the Secular Northstar being related to a regime of law that spends most of its energies in the defense of children, free-range children if possible, and leaves the rest of us to survive or prosper on our own. The protection of the weak is the primary function of law. My point here is that truly intelligent & wise discovery is self-limiting until it that search for novelty or exploration mutates into an obsession which is utterly foolish or a sacrificial devotion which is utterly heroic. Thank god for moderation.

PS. The law should not mandate moderation. That’s the job of society, Church and advice columnists.

I don't read much fiction, but this one caught my eye. Written by a well-studied classicist, Jo Walton, it's a sci-fi journey into the past, bringing together famous thinkers from different eras:

Thessaly: The Complete Trilogy (The Just City, The Philosopher Kings, Necessity) . [ Taste is subjective; your mileage may vary.]

Great recommends ... tossing one back to you ... the category might be called "Mischievous Science-Fiction"; title (there are two because, translated from Japanese, by different publishers, or, perhaps different editions - but same book): "What the Maid Saw" and/or "Portrait of Eight Families". By Yasutaka Tsutsui; thanks ...