When I talk about my desire to read Steiner, which I have put down for the moment because I’m in training to get new job skills and a new job, I am talking about the non-verbal. The non-verbal is the instinctual that we understand as humans with our mammalian intelligence. This is absolutely necessary in an economy that sustains postmodern deconstruction of modern reality - because at the very least, what is modern takes a very long time to establish and sustain. The human and the mammalian intelligence needs a stable environment and ecosystem. Otherwise, our minds get traumatized. Deconstruction is fast. Construction takes time. To thrive in, or to desire the chaos of deconstruction is, not surprisingly, destructive.

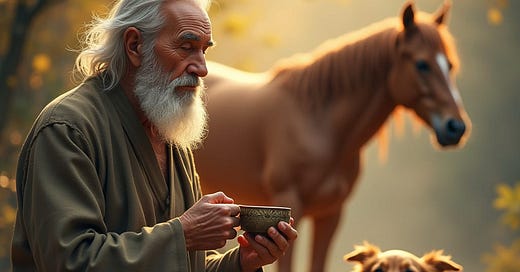

The non-verbal is dance. The non-verbal is a mother humming to her infant. The non-verbal is the dog with the tail between its legs. The non-verbal is the sensory operating system of common sense. It is peripheral vision. It is sweat dripping down your spine. It is a kangaroo squaring up to box. It is your sense of looking at someone sleeping peacefully.

As readers know, I studied the Tao long before I practiced Stoicism. That study allowed me to step away and observe. It helped me make sense of my alienation, of my penchant to disconnect and enter what I called ‘alien observation mode’. I learned to take in the center of gravity of any situation without the desire to grab that for my own advantage - merely for my own peace of mind. Even this writing and my entire process of writing was affected by that process, and I review and process it now, only in public.

It was Yukio Mishima who spoke of the unity of pen and sword, and although I sought that in the Reagan Era, it was merely for philosophical consistency. I was still conforming my body, mind and soul into a unitary self-possession. And similar to monks, my sword play was only dance. Not fighting skill, but self-discipline with some kind of aesthetic of beauty.

The Japanese monk describes Zen in terms of unity, and I see that unity as a settling of the mind that only comes when you are searching for a sense of peace and restfulness in that acceptance of what will be. I quoted Musa last week when he said:

Definitions are not magic spells that bind the political opposition. As I explore at length in the book, even if you introduce a new term into the “language game,” you can’t control how it is interpreted and used once people start engaging with it en masse. If you’re talking about a century-old term that’s already highly-contested, forget about it.

He identifies how we want so much for our symbols and [de]constructed worlds to matter, as if we are all videogame programmers engaged in symbolic world-building. Observe how common it is for energetic youth to spend time and effort in their attempts to ‘make the world a better place’. This is the opposite of embracing the dynamism of the real world with our bare, unprejudiced, mammalian sensory apparatus. We should be hearing what the dog hears, walking where the horse walks, smelling what the pig smells, handling what the monkey grasps.

The modern world is closer to our evolutionary environment than the postmodern world. We can adapt to either, but we still desire the agrarian world. That shouldn’t be surprising. We should prefer a picnic with cheese on the grass rather than hotdogs on the astroturf and that much more than pushing avatars around with our thumbs.

The Zen monk describes that life is to be experienced, not put into words. So at the very least, let these be words that lead you to a pot of tea that you can enjoy in silence.